El Forn de la Calç in Calders, composed of three circular lime kilns and adjacent buildings, has been recognised as a Cultural Heritage Site (Bé Cultural d’Interès Local) and is listed among the 150 most representative sites of Catalan industrial heritage by the Culture Department of the Catalan Government.

The tradition of limestone mining and processing in the area dates back to the 10th century although these kilns were constructed in the middle of the nineteenth century and were active until the end of the 1950s.

These kilns were built in places where there was limestone and firewood. Although they were used intermittently they had a limited life, cooking the limestone also cooked the kiln itself and resulted in a loss of 2 cm of kiln wall for each use.

THE INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE OF CATALUNYA

Catalunya was one of the first European regions to initiate the transition, at the end of the 18th Century, from a pre-industrial economy to the new and emerging forms of industrial production.

The speed and precocity of Catalan industrialisation was due to two main characteristics. On the one hand the emergence of a bourgeois class fully identified with this new process of industrialisation and production

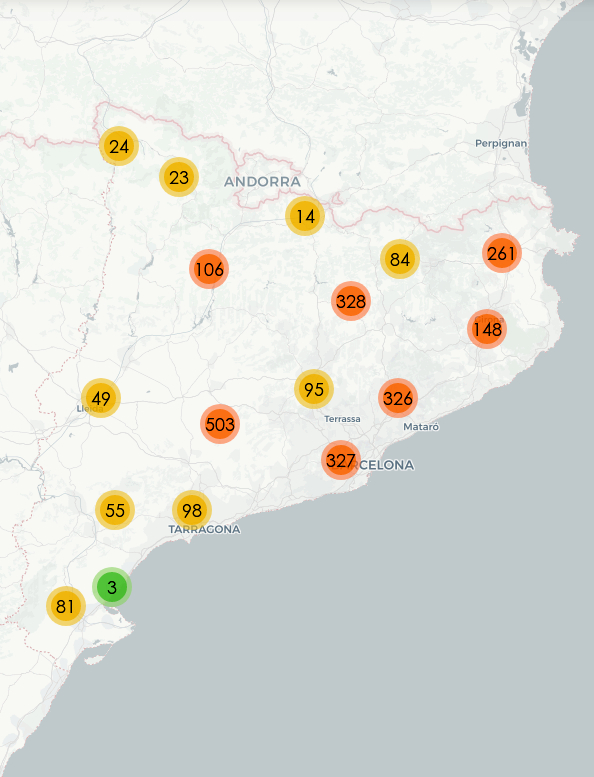

production and, on the other hand, it’s unusual diversity, reflected in both the quantity and variety of the productive sectors affected as well as their distribution throughout the Catalan territory.

This diversity of sectors and locations profoundly affects the analysis and condition of the material and physical remains of the different industrialisation processes in Catalunya, all of which make up what is known as industrial heritage.

The term of industrial heritage refers to all the elements, material and intangible, related to processes of industrial operation and production, including all aspects and contents: machines, buildings, production processes, tools, energy systems, transport systems, storehouses, owners mansions, workers residences, social spaces, archives, graphical and audio material, advertising, social history, maps, plans, commercial documents, trade displays, etc.

THE OLD LIME KILNS

Traces of an ancient technology

In Roman times lime was widely used and it’s extraction well known as shown by the book “De Agricolia” by Marco Ponci Cato (234-145 BC.) which details the construction of a lime kiln. This technique hardly changed during centuries as the kilns used up to the end of the 1950s are practically identical to those of 2200 years ago. These kilns had been common wherever there was limestone but are now not easily found.

Holes in the middle of the woods

There are three holes dug by the side of a track near the Tapiès spring, the remains of the former kilns. One of them is hardly recognisable but we can still imagine their original appearance thanks to the other two.

They are almost cylindrical although the bottom part, called the pot, is a bit narrower due to the step that surrounds it, called the bench. They have two frontal openings: a door for people and to bring in the stone to be cooked, and an opening further up where the firewood was thrown in.

These kilns were built in places where there was limestone and firewood. Although they were used intermittently they had a limited life, cooking the limestone also cooked the kiln itself and resulted in a loss of 2 cm of kiln wall for each use.

The house of El Forn de la Calç, whose inhabitants depended for their livelihood on the extraction of lime, is close to these old kilns. Right beside the house there are three more kilns as well as a fourth called “de raig”; there is also a big limestone quarry.

Traditional kilns, but with high performance

These kilns are bigger and more solid than the traditional ones. They have a covered area in front with a surrounding wall which served as a shelter and gave greater solidity to the kilns. There was also a small room incorporated where the night shift workers could sleep during their pause.

Instead of being dug out in the earth these kilns were built with stone and lime cement, and their interiors lined with sandstone (also a sedimentary stone) which is found in the area and is formed by compressed lime free sand.

This stone does not change with heat so these kilns were not worn away as were those dug in limestone rock.

The kilns generally functioned every other week, so the work was continuous, and the extracted lime was intended for sale. Despite this, the kilns and their system of production were the same as in Roman times.